This year I’m celebrating 30 years as an entrepreneur, and with that round number reminiscing more than usual about three decades of learnings.

My personal journey into startups began a year earlier, in February of 1991, while still a senior in college at Carnegie Mellon. That month’s issue of BYTE magazine focused on the future of laptops, with a series of articles talking not just about the chips, memory, and battery life of laptops, but where the whole computer industry was headed in the coming decades.

My memory is good, but not eidetic, but given archive.org and a magazine that went bankrupt, one can just download the issue and reread it, which is what I did over the weekend.

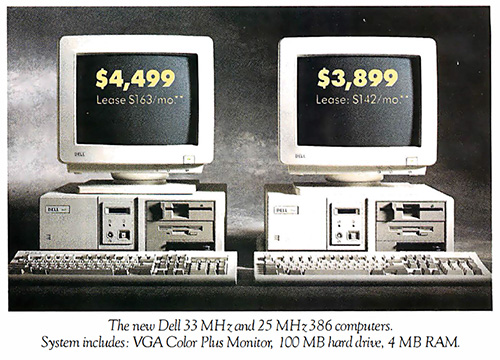

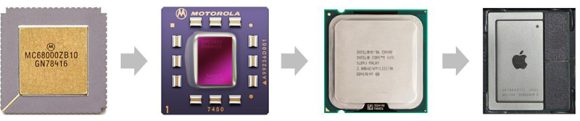

Before diving into the articles, it was fun to look through the ads, to see the state of computing back at the start of 1991. The 386 was the baseline PC chip, with 4 megabytes of memory and floppy disk drives along with small hard drives, all yours for around $4,000 (which is $8,500 today).

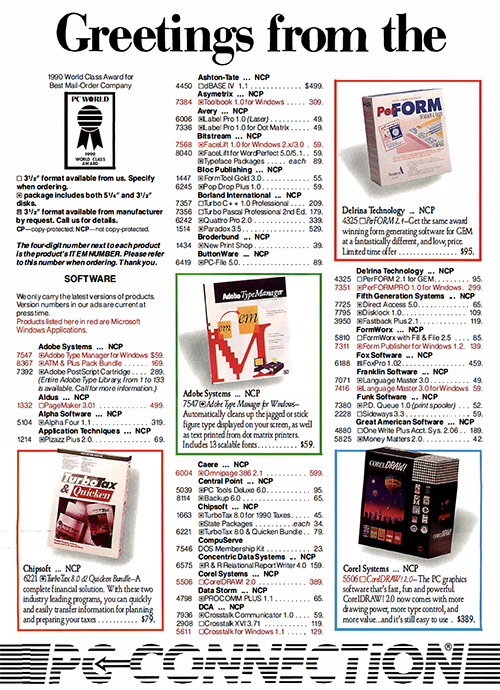

I can’t recall how long its been since I saw a computer ad, but those all felt normal. What I had forgotten about completely was the way software was sold in the 1990s. There were one page and two page ads for products like 1,2,3 and Excel, dBase and Autodesk, plus dozens of others that are long forgotten. But even more common were the multi-page ads listing software for sale, in three column format. Anyone remember PC-Connection? Anyone remember buying software that arrived on a collection of floppy disks?

Moving on to the actual articles, there were four in this article that all talked about the future, and in 20/20 hindsight was is fascinating is to see how wrong all of them were about what was to come. And not just wrong 30 years later, but wrong in the following decade and two.

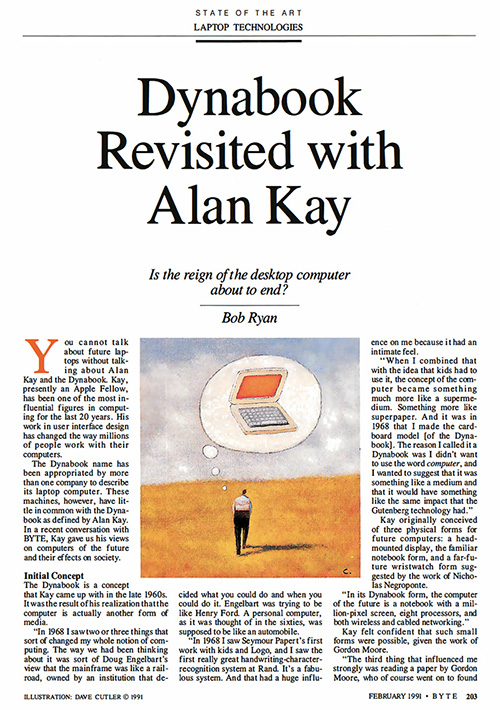

The first was an interview with Alan Kay, technology visionary who was part of the team at Xerox PARC that invented windows, folders, and the graphical interfaces I’m still using to write this blog post.

One of his visions was the Dynabook, a portable computing device. Note the keyboard in the screen shot, and the envisioned size of a notepad. But given that vision came from the 1960s and 1970s, Alan did a stellar job of predicting the eventual portable nature of computing.

However, the article then talks about agents, intelligent software working on behalf of its owner, up in what we’d later call the “cloud”. This vision still hasn’t come true, and probably never will. This idea of sending code up to the cloud was a prediction from the world of mainframe computing, where one big fast computer ran everyone’s code. Instead what Alan (and everyone else at the time) missed was the move toward distributed computing, where everyone has a computer 10,000+ more powerful than those 386 in our pockets, with fast, wireless networks that let us bring data down from the cloud, and where any intelligence is held tightly by centralized services who use that intelligence for their own gains more than ours.

For example, the first example always used for agents was software that would go book a flight for its owner. We solve that today by giving us all searchable access to all the flights. But the pricing on those flights is where the intelligence ended up, maximizing profits for the airlines vs. making our lives simpler and easier. That, and in the end it turns out to be quicker and easier for all of us to learn how to be travel agents than to code an artificially intelligent travel agent to replace what human beings used to do for us.

The next article was the one that changed by life. Ten pages describing what would come after desktops and laptops… pen computing.

Ultimately, Robert Carr and the team at PenPoint was looking in the right direction, but missing nearly all the details of what would actually happen.

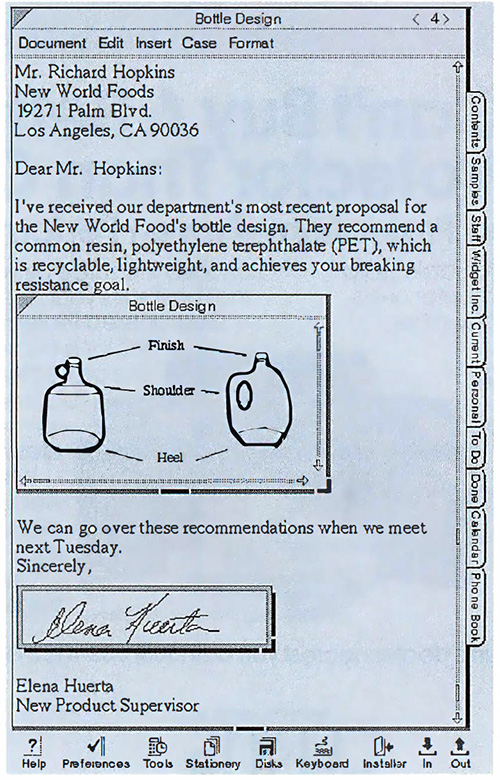

The prediction was handheld, tablet computers operated by a pen, with an interface that acted like intelligent paper, with an interface centered on documents instead of applications.

The root problem in this vision was timing. The hardware was simply not ready to implement this vision. As we saw from the Dell ad, the computers were 386s (and thus too slow), with megabytes of memory (not enough), with greyscale screens (that didn’t work outdoors), battery life of 2-3 hours, and which had to be operated with a pen, as the touchscreen technology was decades away from working well.

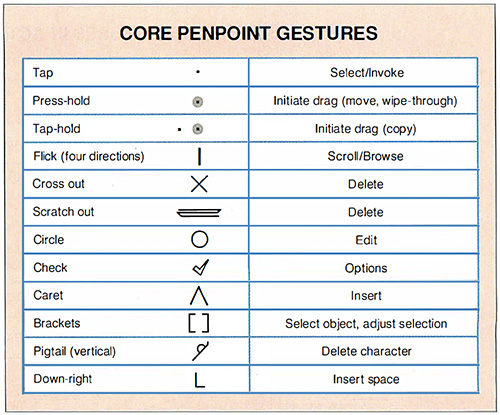

Add to that a brand new operating system that was just too different from everything that anyone had ever seen before, which required memorizing dozens of gestures to function well, with no simpler method for novices to use to get up to speed.

All that, and the handwriting recognition was far from perfect, and the first of these tablets cost $6,000 (which is over $12,000 in 2022 dollars).

What I didn’t see as a 22 year old, first-time entrepreneur was how any of this could fail. My first startup wrote software for PenPoint. I had the first of these devices. They felt as big a leap in computing as the jump from Apple ][ with NO LOWER CASE to Macintosh with windows and mouse. The expectation in 1992 was that faster, lower-cost tablets were coming next year, and while that was somewhat true, it wasn’t until 2010 that the iPad proved the tablet part of this vision correct, just not without the paper-based interface or handwriting or pen.

Visionary article three was one far simpler asking the question, what is the best way to control the cursor on a laptop?

The Mac was by then six years old by 1991, Windows 3 was already popular, and OS/2 was competing for market share too. Mice were the norm for desktop computers. The problem with mice and laptops is, of course, your lap doesn’t have a place to put a mouse. Nonetheless, the norm of the day was to carry a mouse for your laptop, and that was acceptable as laptop batteries only lasted for 2, or at most 3 hours, so you were probably plugging in your laptop anyhow.

This article talked through the alternatives, starting with the Macintosh Portable and it’s innovative trackball. Anyone remember that? Upside down mouse or right side up deodorant ball.

This was before IBM put the “pointing stick” on ThinkPads (in fact, in 1992 the first ThinkPad was a six pound tablet that ran PenPoint), but other laptops had something similar.

Surprisingly, there was one laptop with a trackpad, but lest you forget, trackpads were originally placed between the keyboard and the screen, and the article dismissed them as inconvenient because of that placement.

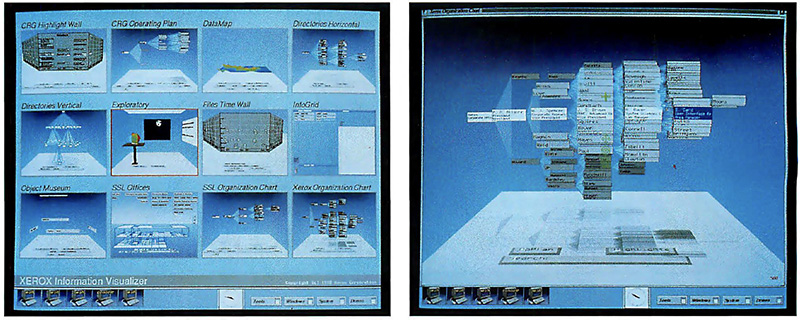

Finally, we finish this issue with an article about the then-current research at Xerox PARC (which not only brought us the Mac and Windows, but also Ethernet and the laser printer).

The question the article asked was what comes next for user interfaces. The thinking was that windows and mice were just a stepping stone to something more powerful. Five decades after they were invented, turns out they still work just fine.

So what did Xerox envision in 1991? 3D. Below are some screen shots of their data visualization. Turns out some of these ideas showed up on future pen computers. Turns out nothing we’ve tried so far works better than windows and mice/touch screens.

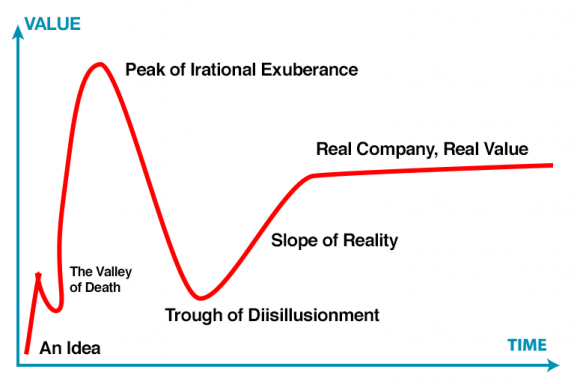

All of this nostalgia is fun, but what can we learn from it? My takeaway is to ask what technology is in the news today that seems inevitable, but like software agents, pen computing, and trackballs, is a technology dead end.

If I had to bet, in software I’d place that bet on the metaverse as a whole, virtual reality as a popular media, and most of augmented reality as a ubiquitous tool. I’ve seen exciting demos for all of those, but ultimately flat screens, windows, and touchscreens are simpler to use, don’t get in the way of the real world, and most importantly, two people using those systems can’t actually interact directly. I suspect the metaverse is “the next thing” here in the 2020s as pen computing was in the 1990s.

Out of the real world, I follow vertical takeoff aircraft, and while I expect we’ll see something in that space be commonplace in the next decade, I doubt it’ll be the rooftop to rooftop inter-city, on-demand, AI-piloted transport that the nascent industry is promising. I suspect it’ll end up too loud, too expensive, and in need of a human pilot. My guess is that this vision is like IBM’s pointing stick. Usable, but far from ideal. Instead, just as the trackpad was hiding in plain site, we’ll find another use of these VTOL aircraft that is in someone’s pitch deck, but not any of the companies that will be first to market.

TL;DR conclusion: predictions are hard, especially about the future, but by looking into the past we can learn how to clear up that foresight.